I was honored to receive an invitation from David Nasca for his Science (is not) Fair book project. He prompted artists to envision alternative medical treatments not limited to what is culturally expected, acceptable, or even medically possible. We were each to create a two-dimensional piece for a curated book that would serve as a kind of alternative medical journal. Much of David’s work is rooted in LGBTQ concerns; this project seemed to question who gets to say what is right in medicine, what a person needs or wants, and how they come to realize those needs. Since I had several months to create the piece, I decided to let ideas pop up naturally. Maybe I would hear or see something that initiated a thread? After months of working on other things, nothing arrived. Ideas or no ideas, I needed to begin.

In retrospect, I think there were two reasons for my initial block. First, I’m not an exceptionally imaginative person; instead of working with a goal in mind I usually focus on the first step before letting the work guide me forward… The second reason for my struggle was the inevitable; the work kept pulling me toward something that was a little too sensitive and too difficult to think about at the moment. I was preoccupied with a close friend’s decision to become a nondirected living organ donor.

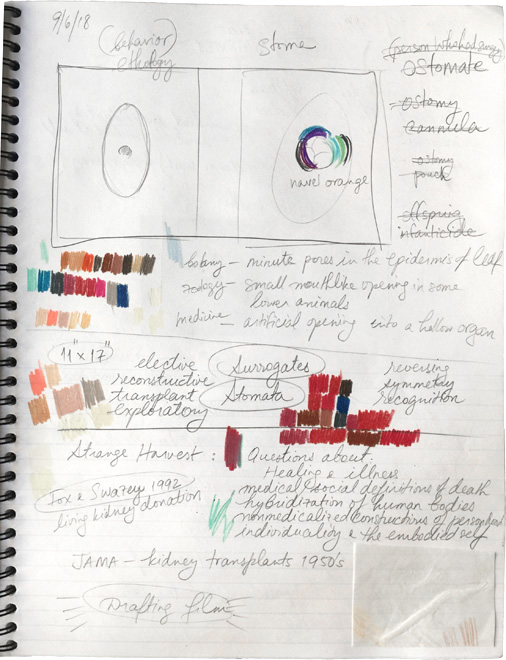

After numerous preliminary tests and psychological evaluations at a top hospital in the region, he got rejected because of kidney stones and a cyst. The tests and evaluations were performed during the course of fourteen months, long enough to build up hope and possibility. This is when I began reading Strange Harvest by Lesley Sharp, a book mostly about cadaveric organ harvesting, and came across a chapter that noted the parallels between organ donation and surrogacy:

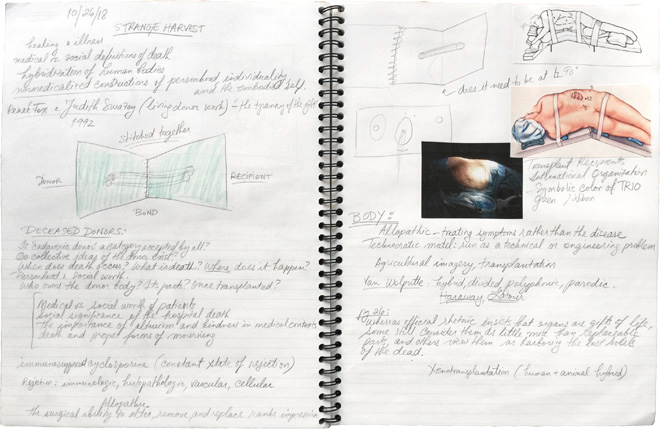

“A unique property of organ transfer [. . .] is that it can create new identities while sidestepping human sexual reproduction altogether. Also, both gestational surrogacy and organ transfer draw anonymous strangers together into potentially complicated forms of blood relatedness. Both are about children as well. Whereas a fetus grows inside a surrogate, in organ transfer the transplanted body fragment nurtures the organ recipient, whose body fosters the postmortem trajectory of the donor. The recipient in turn now supports the vital organ, too.” (Sharp, 2006, pg. 202)

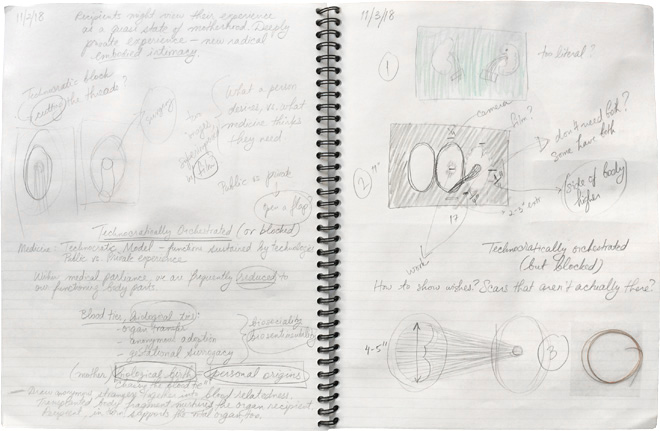

What I initially perceived as a fun project ended up taking a darker turn. I was reading about “technocratically” orchestrated procedures, things that are only possible due to high-tech progress and innovation, operations entirely directed and regulated by medical professionals. Was my friend’s procedure technocratically “blocked”? Would he have gone through with this procedure if he could have done it himself, if others didn’t have a say? How is a line drawn between what a person desires vs. what medicine thinks they need? There were many other factors and questions involved in this situation, things too personal to discuss here.

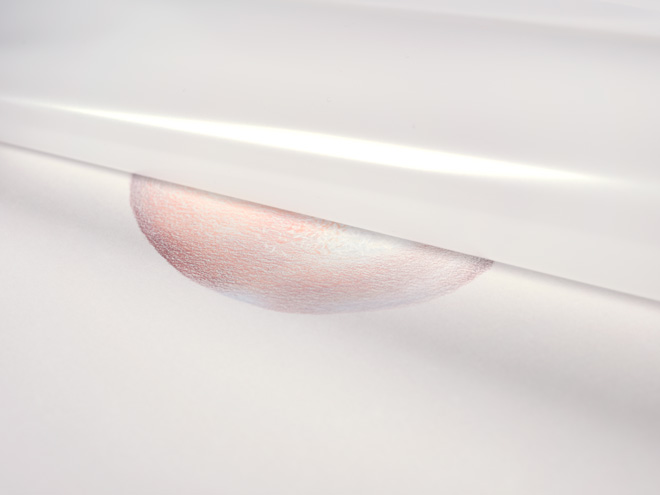

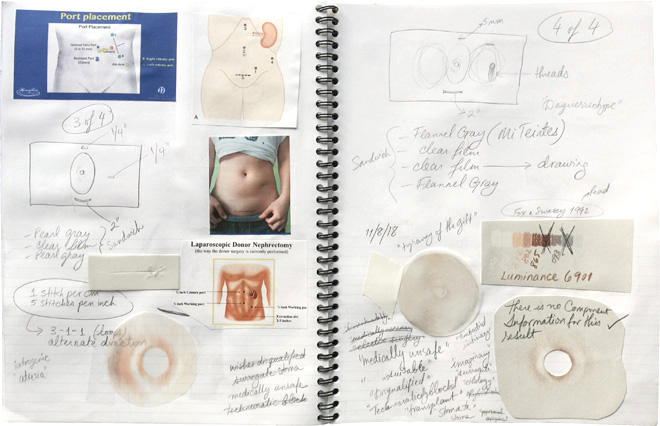

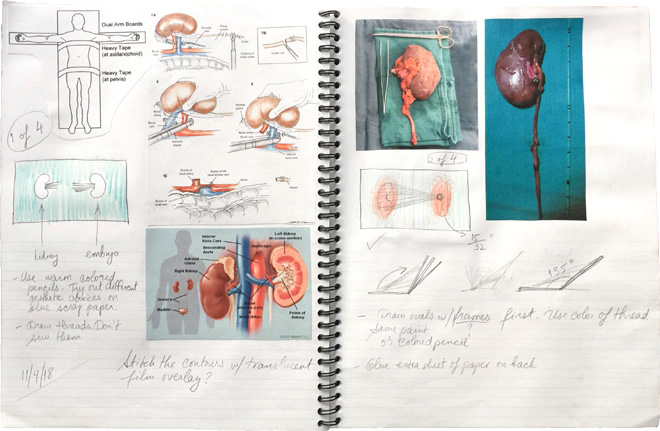

The surgery would have been laparoscopic, through the belly button, so I decided to use navel oranges as models for illustration. I bought a bag of oranges and chose flesh-tone colored pencils instead of more accurate colors. Many of my aesthetic choices referred to things I had done in the past: oval cutouts, scientific illustrations on toned paper, parallels between botanical fragments and human flesh… I tried mat board, layering, sewing, transparencies, isolated navels, various paper colors and textures, and other iterations before I decided to simply draw one full orange in the center of a gray sheet.

The most disconcerting aspect of the finished piece was the void in the middle of the illustration, the blank navel. Like the unfulfilled organ donation and unfulfilled donor-recipient kinship, this part of the drawing felt incomplete, unrealized. I decided to cover the entire sheet with translucent drafting film in order to create a sense of denied access and haunting. Then I incised and stitched the two sheets together in four areas. The locations of these incisions in relation to the navel are based on one common type of laparoscopic nephrectomy. For the stitches, I chose clear nylon monofilament and the 3-1-1 knotting method often used in medical suturing. The title of this piece comes from my friend’s final test result, the one he received right before he was rejected as an organ donor. In typical alienating medical jargon, one of the report sections read: “There is no component information for this result.”

Work Cited

Sharp, Lesley A. Strange Harvest: Organ Transplants, Denatured Bodies, and the Transformed Self. University of California Press, 2006.