Back when I was in residence at the International Museum of Surgical Science (2013-2015), visitors routinely stopped by my drafting table to see what I was doing. Among them was a medical student who told me about a social networking app that resembled Instagram but featured only medical case studies. Several apps fit this description, so you’ll have to guess which one I’m talking about. All of them are relatively strict with regard to distribution, patient privacy, and copyright policies.

I joined the app as an unverified user and found myself scrolling through image after image of injuries and diseases, some of them unspeakably horrifying. Each image was followed by a caption with information about the patient, and—just like Instagram—each image had a series of “likes” and comments from all corners of the world. The only people actively using the app were health professionals—doctors, nurses, surgeons, and the like. I just observed without posting, but I was able to bookmark specific cases in order to look at them later.

My artwork already focused on the body and its visual representation, so I expected the app to become useful in my artwork somewhere down the line. Around this time I was also reading The Body Multiple, a medical anthropology book by Annemarie Mol in which, to put it simply, the author describes how one medical condition might mean very different things depending on whom you ask. Many ideas in the book resonated with what I was seeing on the app.

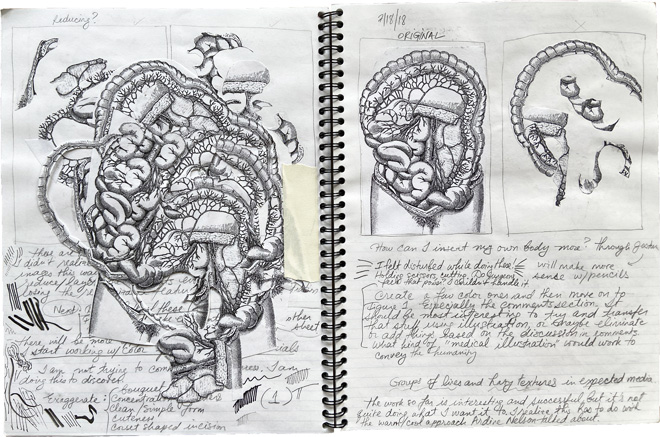

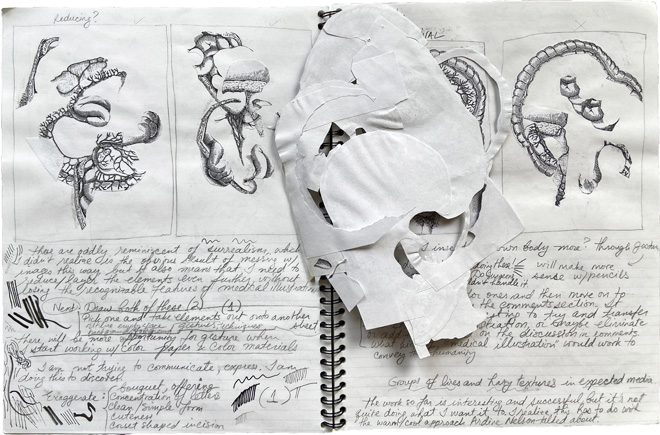

A couple of years went by, and my attention turned to one-off projects in sculpture, ceramics, and oil painting. In the summer of 2018, I spent a month in relative isolation at a residency in the south of France. I was yearning to get back into drawing, so I made some photocopies of antique medical illustrations—cutting them up, collaging in my sketchbook, and then drawing the collages. Although the process led to some compelling pieces, it also felt like a dead end; the work felt impersonal.

This is when it occurred to me to look at that app again. What attracted me to the app in the first place was not the grotesque voyeuristic element of gawking at medical conditions, but just how frank and informal most of the comments were—ranging from possible diagnoses to advice, anecdotes, expressions of empathy, puns, and jokes. People were connecting with each other through their profession but also connecting to the patient and trying to make sense of what they saw on an emotional level. I was drawn to the cultural aspects of each case: how much could be inferred by reading between the lines, the implications of a patient refusing treatment, the coping mechanisms, systems of support, tensions and disagreements, degrees of worry and concern. All of these (usually hidden) relationships in medicine were uncovered by the app.

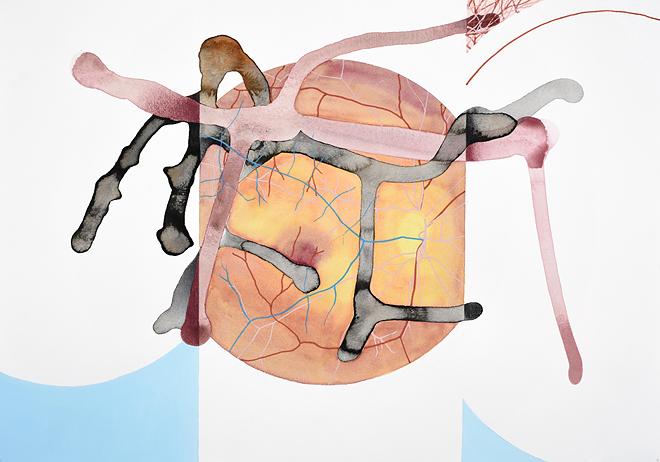

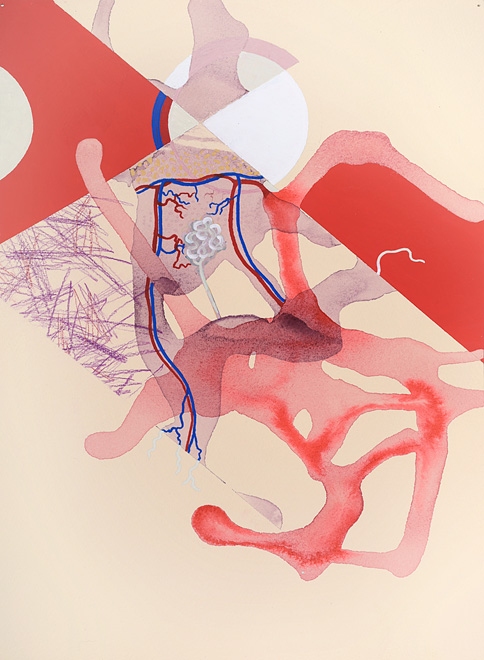

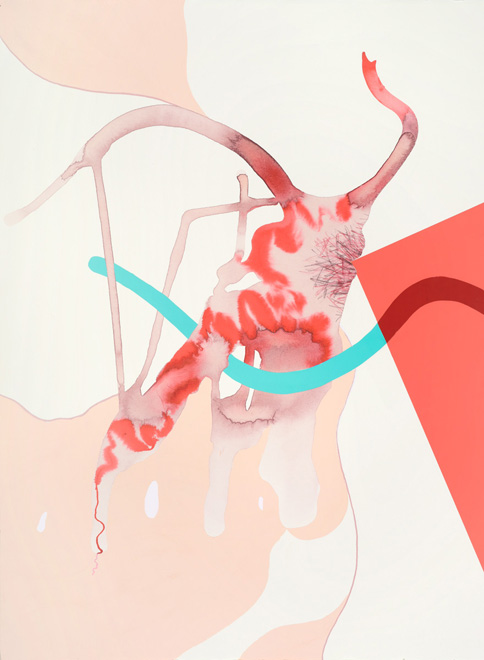

As with most of my work, I began this new project by setting some parameters. The ideas called for works on paper, but not any consistent scale or medium. I began each drawing by adding two vertical lines in order to create a visual interruption or membrane. I wanted my drawings to have a similar feel to the app: information passing back and forth, clustering, filtering, and transforming like a game of broken telephones. The lines delineated a rectangle with an aspect ratio of 16:9, just like the smartphone I was using. After I added these vertical lines to a few pieces, I abandoned them and tried other experiments: leaving no blank paper, leaving a lot of blank paper, using the entirety of the ink blob instead of leaving some of it undefined, using no representational images, etc. It was important to me that this project be based entirely in a physical medium without any digital elements. I was mixing media and creating surfaces and textures that didn’t translate well online (as is the case with most works on paper). I liked the idea of bringing bodies back into the physical world by observing how they were depicted and talked about online.

What follows is a selection of case studies from hundreds of posts. I chose them mainly because they were in some way questionable or curious. They brought to light the ways in which healthcare cannot be neutral or impartial; each entry had some degree of cultural bias—sometimes subtle, sometimes blatant. I was struck mostly by the details included or excluded in each caption, as well as the comments:

A chest X-ray showed a tiny stylized silhouette of a cat in the center of the image. The caption explained that a 10-year-old female had told her parents that she swallowed a “cat.” The toy turned out to be a Monopoly play piece. Several commenters made jokes about how far the cat had to travel before “Passing Go.” One commenter worried about perforation of the intestines, but most didn’t think it was a concern since there were no sharp parts. Another commenter expressed concern regarding the patient’s age-inappropriate behavior.

A retinal scan showed blood vessels branching out from the right side of the image. The caption stated that the blood vessels were unusual in that they didn’t branch apart immediately but traveled across the retina first. There were only a few comments—some mentioning the possibility of diabetes. One commenter requested an explanation as to the significance of the image. The original poster replied that there was no significance other than it being unusual.

The images were medical scans (either X-rays or CT scans) of a skull from different angles. A metal spring from a pen was visible inside the right eye socket. The caption described a male patient in his 40s who impulsively stabbed himself in the eye while at work. His diagnosis included the phrase “Appel du Vide.” Most of the comments expressed shock and horror.

The image showed an extended forearm with blistering and burnt skin, photographed from above. A few areas looked completely raw as though the skin had melted off. Below the arm, in the blurry background, there was a canvas sneaker with a yellow-and-black leopard skin pattern. The caption explained that a 16-year-old female patient recently came back from a trip to Morocco and presented with the rash. Commenters mostly wondered if the rash was caused by a parasite, until someone pointed out that it vaguely resembled a panther. It turned out that she had purchased a temporary tattoo from a street vendor in Morocco and developed a severe skin reaction from it.

An X-ray of a leg in profile showed severely misaligned broken bones that—over a period of time—formed what looked like a large knob of bone tissue. The caption mentioned chronic leg pain and facetiously asked if anyone could spot the reason why. The comments expressed outrage and disbelief. One commenter asked which country the post was coming from. The original poster answered “USA” and added that the patient does not want surgery, so painkillers were the only option. This triggered a string of arguments in which some commenters were outraged at the idea of treating medicine as an “à la carte” menu. Others pointed out that medical care is expensive in the United States—that the patient might have a limited income, and to call them a “drug-seeker” would be unfair.

Two X-rays showed a foot with a large metal pin lodged between the toes. There was an additional image of the brass pin photographed on a gauze pad soaked in blood. The caption stated that the patient got angry and kicked a sundial while gardening in flip-flops. One commenter joked that the sundial didn’t deserve it. Another wrote that it must have been guilty of something, to which yet another commenter replied that it was guilty of time. Yet another commenter evoked St. Francis de Sales and his guidance to always stay calm.

The photograph showed a badly mutilated, barely recognizable arm, with several small, solid gray, digitally generated rectangles covering parts of the flesh. The rectangles were automatically added by the app’s facial recognition software in order to cover up possible faces in the image. The caption stated that a 77-year-old female was checking her mailbox when her foot slipped off the brakes. Her arm was “degloved.” Paramedics arrived at the scene and applied a CAT tourniquet. Commenters mostly expressed sympathy and shock. One commenter hoped that she had received something good in the mail that day to offset the injury. Another stated that they’ll be walking to their own mailbox from now on. Several people asked how she fared, but the original poster didn’t know because the patient had been transferred to another unit.

An X-ray of a skull in profile showed a small mass near the top edge (parietal region). The caption stated that an 18-year-old African American male walked into the ER with a bleeding head wound. The bullet had ricocheted and got stuck in his scalp. He was transferred to the trauma center for removal, and the doctor told him to go buy a lottery ticket. Some of the commenters joked that the lottery ticket was going to be a loser because his luck was all used up. Others expressed astonishment and disbelief at the incident. Many commenters posted their own stories about bullets and luck.

The photograph showed a bare back from the neck down. The person was wearing dark boxer briefs with a blue waistband. The clothing brand name was masked by scribbling over the image with a digital pen. The patient had extra fat folding over the waistline, and the pale skin on his lower back had a lacy rash with subtle purple striations. The caption explained that the patient had lower back pain and stiffness, and had recently lost 60 lbs after being advised to do so. A few commenters recognized that the rash was caused by a heating pad. The original poster confirmed: the patient used a heat pack every evening to get the Minotaur out of his body. The Minotaur was allegedly a bad influence and made him do bad things. They subsequently adjusted his antipsychotic medication.

The photograph showed a hairy lower leg with a small red curvilinear rash. The caption stated the diagnosis as Cutaneous Larva Migrans (hookworm). A commenter described the rash shape as an elephant with wings, while someone else added that it was a pink elephant with wings (followed by a laughing emoji). Another commenter described it as the shape of a bull’s head. Ultimately someone wrote that this was “an artistic larva.”

The photograph showed a closeup of the patient’s back with a vaguely triangular rash and a few blisters in the center. The caption explained that the patient worked in the hospital laundry unit, and that the rash appeared after a tingling sensation. The diagnosis was still undetermined and the original poster asked for opinions. Most commenters insisted that this was a burn—more specifically a steam iron burn. The original poster explained that the patient denied being burned, but the commenters speculated that this was due to horseplay, and that the patient was lying, trying to cover up a work accident, or that this was a “stupid prank gone bad.”

The cases were astounding in how much they revealed about illness, intersubjectivity, representation, empathy, kinship, priorities, values, and a million other things. Working on this project opened up new avenues and left me with an endless stream of questions.