For the past year or so I have been drawing antique toys – an unexpected departure from my ongoing work with medical illustration. These drawings have mystified people both in person and on social media, so I’ve decided that this is as good a time as any to describe the ideas I’ve been working with and the path that led me to this series.

My residency project at the International Museum of Surgical Science, titled The Oval Portrait, commenced in late 2013. Early in the residency, I devised some new technical approaches, including how to cut ovals, rotate them, and re-position the buckled paper. I also fleshed out some general ideas regarding my role as an artist in the museum and my relationship to the collection.

I began to gain momentum while working on two pieces that were based on a specific artifact: the Lindbergh perfusion pump. After completing this work and examining several related items, I decided to switch gears and find something new to work with. The museum is filled with fascinating artifacts related to the human body. An iron lung, a large bladder stone, an X-ray shoe fitter, ancient Roman speculums, trephined deformed skulls… These and a number of other display items equally suited my interests, making it very difficult to choose. I was looking for something that moved me on an emotional level, something that had left an impression on me even before my formal affiliation with the museum.

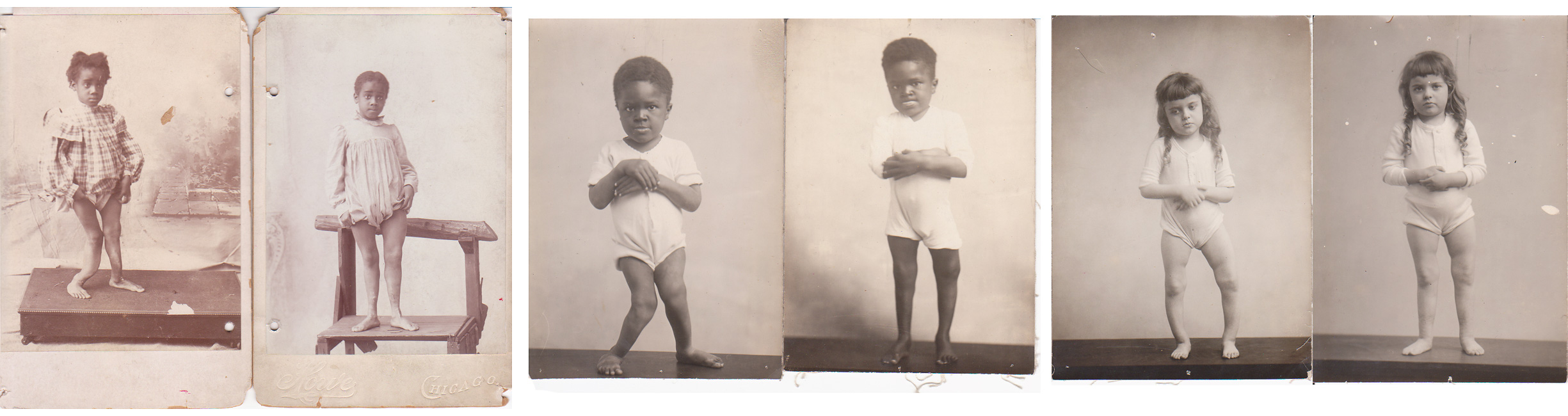

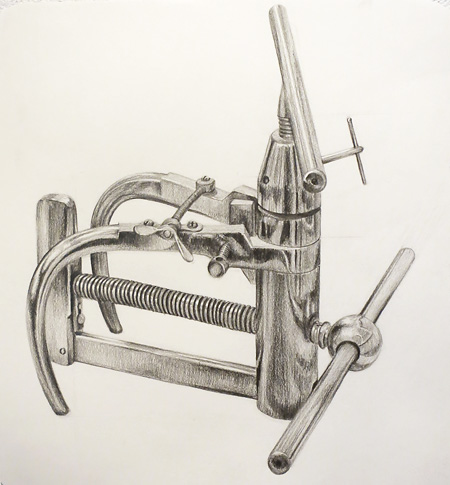

One of the most disturbing items in the collection is the Grattan Osteoclast, a.k.a. “bone crusher,” a crude stainless steel device used for fracturing and correcting the legs of young children who had been afflicted with rickets or a similar bone-deforming illness. The Osteoclast was surrounded in its display case by before-and-after photographs of children that had the “bloodless” procedure done in the first couple of decades of the 20th century. I asked the former curator Lindsey Thieman and curatorial assistant Peter Rosen to pull any other artifacts and documents related to the bone crusher. They found a number of additional photographs, a wooden case for the device inscribed “Elven Berkheiser,” an accompanying key to unlock the case, and several articles by a surgeon named Wallace Blanchard. Both Berkheiser and Blanchard worked in Chicago at the Home for Destitute Crippled Children where they performed the procedure on a few hundred young patients.

What struck me immediately while going through the reference materials was the expression on each child’s face – the “after” photograph somehow looked hardened, as though the child had grown up too soon. Blanchard, however, came to a different conclusion: “Attention may be directed to the fact that the restoration of symmetric legs has been accompanied in every case by a more reliant expression of the face and a more confident poise of the head.” In another journal article, he claims: “Nothing gives more joy to a bedridden crippled child than the prospect of standing alone and being able to walk, with a further prospect of being able to do its share of work in the world.” Some of the articles even describe disagreements between surgeons, notably a surgeon from Vienna whose procedures were criticized by the Chicago school. While looking through various websites related to the Home for Destitute Crippled Children, Lindsey and I came across an entry on Google Maps that showed where the home was located in Chicago. Oddly enough, a week later the entry was gone.

Having looked at a number of articles and objects related to the Grattan Osteoclast, I was ready to begin drawing. But where and how would I begin? I decided to create a sketch of the instrument, not only in order to pass the time while processing everything that I had read, but also to maintain direction and focus, and to potentially learn something about the Osteoclast that couldn’t be gained through conscious deliberation. I wrote a previous entry about this phenomenon that is unique to drawing, how it can sometimes provide an incommunicable insight that cannot be gained by simply looking at the subject or even reading about it.

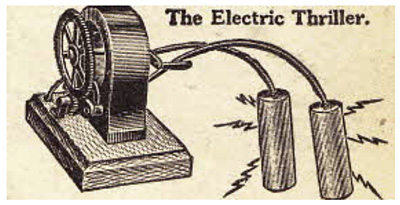

As soon as I completed the 4-hour study of the instrument, I looked at my drawing and came to a bizarre realization: when drawn in this smaller scale, the instrument looked like a wind-up toy. This immediately took me to several questions. What kinds of toys existed between 1890 and 1930 while the Osteoclast was being used? Who were these children? What did they play with? I started looking up online antique toy auctions and finding doll repair websites that showed before-and-after pictures of mostly blonde and blue-eyed antique ceramic dolls. I also discovered that plastic didn’t appear on the market until the 1930s, which meant that toys before this period were made of wood, tin, ceramic, and fabric. I came across everything from rocking horses to building blocks, wind-up toy cars, jacks, spinning tops, and the strange “Electric Thriller.”

After looking at the toys, I went back and took count of all the Osteoclast case studies combined, both from the journal articles and the before-and-after photos. There were 16 children in total, all documented by first name and last initial. One anonymous child was just referred to as “a boy,” presumably because his was the only case in which the surgery did not go too well.

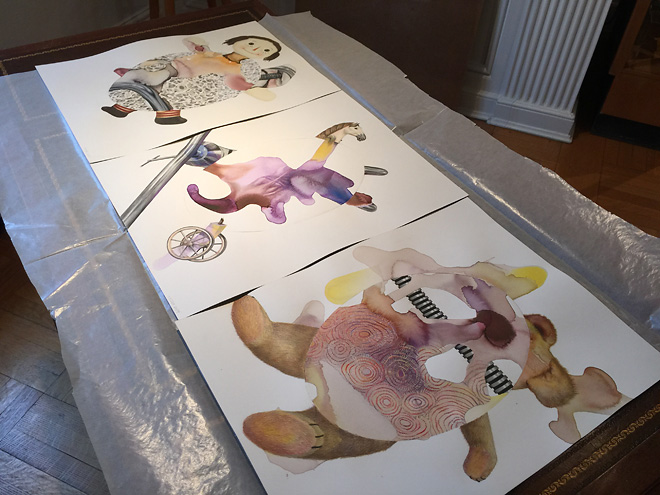

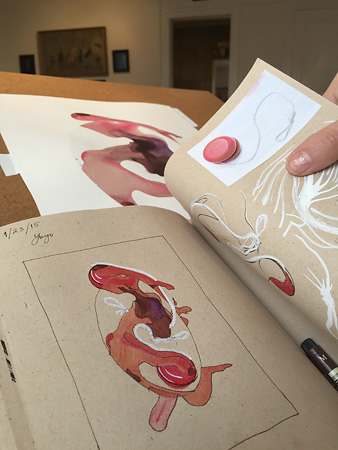

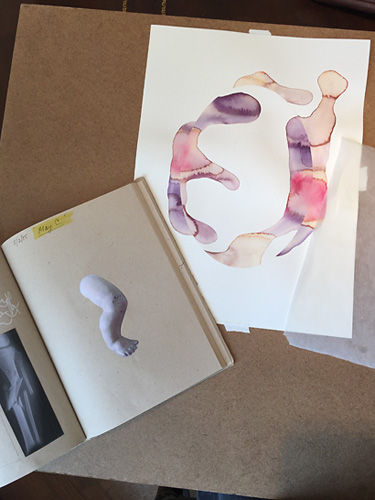

I decided to create a number of small 16”x12” inkblots with rotated ovals. The plan was to focus on the children rather than the surgeon or the instrument – to create a portrait of each child, a personified snapshot of a moment in the child’s life. Although nothing specific was written about these children other than their ailments and the corrective procedure they required, I wanted to create work that would draw attention to their humanity. I ultimately decided to create 16 drawings. Each drawing would include a toy, a piece of the Osteoclast, and some bone tissue.

While reading about the case studies, I came across words and phrases like eburnation, coxa vara, supracondyloid osteoclasis, epiphysis, osteokampsis, and “grape vine” legs. Each child had a unique complication. As I shuffled through my inkblots and found toys that matched the ink both in color and shape, I also tried to find connections between the inkblots and case studies. I started out with a polished toy marble, and used it to reference a child that experienced eburnation, a case of hardened and polished bone. From there I drew a winding key with lacy bone cells; a wobbly clown with no legs; tinker toys; Raggedy Ann with a bone tissue dress; a broken stick horse; a dismembered teddy bear; two swirling yo-yos; Lincoln logs; a ballet dancer with perfect spinning-top legs, and a severed porcelain doll leg. I’m currently working with an image of a tricycle that will be misassembled, which leaves me with four drawings to go.

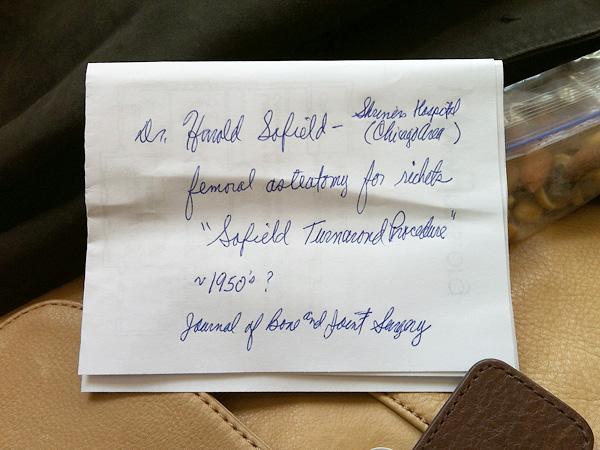

I’ve had a remarkable experience working on this series, with numerous conversations sparked with museum visitors – some excited, some perplexed, and some afraid. One elderly man, a retired bone surgeon, approached me with the story that he had performed dozens of pediatric surgeries involving a very similar procedure that he and his colleagues called the “shish-kabob method.” He handed me the note pictured on the right. Various side-projects and collaborations have emerged from this body of work, and over the past year the museum itself has gone through a lot of changes, including the hire of a new curator, Collin Pressler, who has been very generous to provide a larger residency space on the 4th floor of the museum and to bring in more artists. I’ll write more about this transition soon. I feel lucky to still have access to the museum after a long run, and to work with such great people who share my interest in the proliferation of art, especially in places where it might be unexpected.